|

|

The official website of Until Our Last Breath: A Holocaust Story of Love & Partisan Resistance published by St. Martin's Press and maintained by author Michael Bart. |

Vilna, the Capital of Grand Duchy of Lithuania"Vilna no longer exists...Like Troy, the Vilna I knew, the Vilna described in Jewish annals, now lies beneath the debris of history, beneath layers of death and destruction."1 Introduction:There is an old saying that comes from Jewish Vilna, "go to Lodz for money, and come to Vilna for wisdom."2 A man from my father's hometown of Hrubieszow, Poland, a small stetl located near the major city of Lublin recently said to me,

"Vilna was the most famous city in Poland. It was an honor to say you were from there."3 Vilna at its very height had a rich Jewish cultural life with vibrant institutes of higher learning. Prior to the Nazis' invasion of Vilna, the city was known as

the "Jerusalem of the North." At the time of Vilna's liberation in July 1944 the majority of Vilna's Jews had been shot and killed at the pits of Ponary by the Nazis and local Lithuanian collaborators.4 Close to half of the Jewish

population of Vilna had already been murdered before the sealed ghetto was even created in September of 1941.5 Once the Nazis

implemented their program for the Final Solution of the Jewish question in Europe, the Jews of Vilna were amongst the first in line to be destroyed. The Nazi invasion also ignited the seizure of Jewish homes owned for generations, their personal possessions, and family heirlooms and implemented a quota to destroy seventy percent of all the Jewish books housed in the city--thus attempting the full destruction of the history,

identity and memory of Vilna's Jews.6 The Jews of Vilna found themselves completely surrounded in an environment with both Nazis and hostile locals, and were doomed. However, the hopelessness and defenselessness of Vilna's Jews does not imply they willingly

succumbed to their destinies. Contrary to the modern day vision of passivity, was resistance on various levels--all of equal importance. There was spiritual resistance with the creation of theater, music, and continuing education within the ghetto;

there was the 'paper brigade' that helped save what became the remnants of Vilna's books; and there were young leaders who helped organize a unified movement of resistance in the Vilna ghetto. Discussed here will be numerous aspects of resistance; however

the main focus is on the various political groups of youth and young adults that secretly met within the newly created ghetto and began to arm themselves and discuss ways to fight back against their oppressors.

In trying to flesh out the facts about the Holocaust perpetrated

in Vilna and the losses incurred that provoked a resistance movement, there first needs to be an understanding of what the city of Vilna was, before the Nazis invaded. Readers of the Holocaust, often ask themselves how such a tragedy of this magnitude happened? Somewhere within early Lithuanian and Polish history lies the answer. The following is a guide to the Jewish communities' over five hundred years existence in Vilna, a city and a community of people that has been erased from many world history and geography text books--a city and community no longer to be found.

Some today, including myself, still refer to the city as Vilna even though the name was changed during WWII. My mother was raised under Polish rule when the city was called Wilno. However, when my mother and father left the city after liberation in 1944, the Lithuanians had renamed the city Vilnius, a name that was kept in place by the new Soviet occupiers. As a second generation of Holocaust survivors my mother often referred to the Polish name Wilno, but more often in my family the city was referred to as Wilna, or its English version Vilna since that was the name my mother's family had used for generations including my three great uncles who fled czarist Russia to America between the years 1905 and 1910. For the purpose of this historical guide, the city will be referred to as Vilna.

Michael Bart

Back to Top Vilna, the Capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania"It is our wish that the Jews, who we take under our protection in our own interest as well as the State, shall feel well and safe during our fortunate reign."7 By: Bonnie BartIn 1322, Lithuanian Grand Duke Gedimin built a fortress castle on a foundation attributable to the Normans dating back to the tenth century.

By 1388, Jews began settling in the neighboring town of Troki, and trickled into Vilna, mostly during the end of the fifteenth century.9 Two waves of immigration brought Jews to Vilna; the first was through southern Russia to the east and the second was mostly from Germany to the west.

In 1401, Poland and Lithuania agreed on a political alliance, however that meant that Lithuania overtime became dependant on Poland's economy.10 The Jews lived under a 'special protection' issued by a charter

in 1388 that granted Jews positive rights. The charter was first given to Polish Jews by Grand Duke Boleslav the Pious in 1264, and confirmed again by Polish-Lithuanian King Casimir Jagiello in 1334 and 1357. There was a paragraph in the charter issued by the Pope forbidding any accusations to be made against Jews of blood libel and damage to a synagogue or a Jewish cemetery was to be fined.

However, a year later the Polish Cardinal Olesnicki abolished the charter after the German Teutonic Order defeated the Polish army. The Cardinal blamed the defeat on the King's charter in favor of the Jews who worshipped their religion differently than the Catholic Church. All the former privileges granted

to the Jews were then annulled in what became the Statute of Niexzawa. Even though, the liberal-minded monarchy ignored the Statute during his lifetime, King Casimir was later succeeded by his two sons who confirmed the Statute--thus giving control over rights of Lithuanian Jews to the Catholic Church.11

Back to Top The Polish-Lithuanian Union, "Union of Lublin" (1569)

The subsequent monarchy was elected by the nobles, and no longer had power over the military, financial, administrative

and political affairs of the State. The Jewish minority became subjected to the hostilities of the Catholic Church and the nobles; and the middle class Christian tradesmen and craftsmen looked at the Jews as competition.14 By 1573, an organized Jewish community in Vilna had built their first synagogue and called it the City Synagogue. By 1592 the city had a street called Jews' Street. The middle class tradesmen simmered with resentment towards the Jews of Vilna

and attacked the synagogue and the shops on Jews' Street on May of 1592. The Lithuanian Supreme Tribunal ruled that the culprits pay the Jews for damages and spend six weeks in prison. The tradesmen ignored the ruling, however one year later agreed on a settlement. After several more attacks by the tradesmen, King Sigismund III addressed an injunction

in 1632 forbidding violence against Jews or interfering with their trade.

When King Sigismund III's eldest son, Wladislaw IV, granted additional trade rights to the Jewish community in 1632, he established a ghetto area for the protection of Jews. The Jewish quarter was comprised of Jews' Street, Butchers' Street, both sides of St. Michael Street and Niemiecka. In addition, Wladislaw IV allowed for a

synagogue to be built of stone that would replace the original structure of the City Synagogue. The courtyard of the Great Synagogue became the heart and the most frequented area of the Jewish ghetto. The rights granted by the King were viewed by the tradesmen as a mark of goodwill towards the Jews. As a retaliatory move, the tradesmen mobbed the Jewish shopkeepers and attacked the Jewish cemetery. For over 50 years the Jewish community in Vilna struggled with the Municipal Council and the tradesmen to secure rights to dwell, work, and trade in the city.15

Back to Top The Cossack & Muscovite armies (1653-1661)

After the Cossack troops from the Ukraine and the Muscovite army from Russia overran the eastern parts of the Grand Duchy in 1653, the troops occupied Vilna in 1655 and set the city on fire. The fire raged for seventeen days and consumed the Jewish quarter.16 When the Polish army recovered the city in 1661, Vilna's population was devastated.17 In the aftermath of the devastation, the struggle increased between the local tradesmen and Jews over trade rights.

On many occasions the Jews were attacked or raided by members of various guilds such as salt vendors, butchers,

glaziers, fisherman, grain, tanning, and the furrieries.18 The Jews had a hard time securing work. However, three subsequent Kings were fair and protected Jewish interests. According to the municipality in 1645 there were about 2,620 Jews and 12,000 Christians in the city of Vilna. In 1662, after the Cossack invasion there were 415 Jews left in the city.19

Back to Top The Commonwealth in Decline

The power of the Commonwealth uniting the two states first created in Lublin in 1569, entered a decline in 1648 for two reasons. First was the Cossack-Russian occupation, and second was the Swedish invasion in 1655. The later part of the seventeenth century was marked by increasing hostility on the part of the tradesmen towards the Jews in Lithuania and Poland. The hostilities were ignited by wars, and the aftermath of poverty, and anti-Jewish feelings fomented by the clerics who disseminated the story

of an alleged blood libel case brought against the Jews in Vilna and Bialystok in the late fifteen hundreds.20 The clerics and Jesuit priests actively tried to get the Nobles to pass "special laws" against Jews. King John III Sobieski tried to bring tolerance and suppress the anti-Jewish riots, and sent troops when

he heard there was a pogrom carried out by the tradesmen against Jews.

Back to Top The Great Northern War swept Northern & Central Europe (1700-1721); and the Great Plague in Vilna (1708-1710)At the end of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the city of Vilna experienced a series of disasters. It was a period of civil strife, war, famine, plague and fires. The stress and fear encountered by Vilna's inhabitants was created by the Great Northern Wars. A coalition of states that included the Russians, Danes and Saxon-Poles was created against Sweden's fifteen year old King, Charles XII.

Sweden occupied the city of Vilna from 1702 to 1708, and imposed heavy taxes on the inhabitants to build a military base for a planned invasion toward Moscow.21 The Great War that swept Northern and Central Europe ended the Swedish Empire, and left the Russians the dominate power in the region. The successor of John Sobieski, King Augustus II finally restored the peace in the city of Vilna in 1709.22 Six years of occupation resulted in famine between 1708 and 1710, and was followed with an outbreak of Plague that resulted in many deaths.

With Vilna's hardships, Jews had a difficult time paying the poll tax due and were granted a ten year moratorium by the monarchy. In the aftermath of famine and Plague, a series of fires broke out in the center of town that destroyed almost the entire Jewish quarter, damaged the Great Synagogue and various other Jewish communal buildings, 469 homes, 15 mansions, and 12 churches.23

The Jewish community continued to struggle with the tradesmen over trade rights. On May 29, 1738 King Augustus III confirmed several charters for the Jewish community. The charters extended the rights of Jews to open shops and retain liquor trade for twenty more years. However the Municipal Council protested, and on December 18, 1740

the old charter of 1527, the Statute of Niexzawa, was reinstated--the Jews were forbidden to live in the city's urban areas.24 With underlying tension over trade rights, the tradesmen took the next step and threatened to expel the Jewish community from the city altogether. After many proposals and counter proposals, the municipality laid down the conditions of a settlement: Jews

who lived beyond the Jewish quarter would be punished by the demolition of their homes; they could only sell certain items in their shops, and could only possess small weighing scales. The chief purpose of these conditions were to severely limit Jewish trade, and in the years following the restrictions increased.25

Back to Top The Constitution, Polish - Lithuanian Federal State (1791 - 1795)The Constitution adopted on May 3, 1791 was an attempt to reform the Commonwealth in order to quell internal and political instability. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth encompassed not only Poland and Lithuania, but the territories of Belarus and Latvia, large parts of the Ukraine and Estonia, and pieces of what is today, western Russia.26 By 1800, the world's Jewish population was about 2 1/2 million, including about 250,000 Jews who settled in almost every town and township

in the Grand Duchy--becoming the largest populated territory of Jews in the world.27 The attempted reforms by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth failed to stabilize the State. The vulnerability of the Commonwealth allowed the federal state to be partitioned in three stages by the neighboring Russian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Monarchy. By the second partition in 1793, the city of Vilna was annexed to czarist Russia. By the third partition in 1795, parts of the Polish-Lithuanian federal state were incorporated into Prussia.28

Due to czarist Russia's takeover of Vilna and to Vilna's Jewish community's discontent with the Polish treatment of Jews, the Jews of Vilna rallied in support of Lithuanian patriot Thaddeus Kosciuszko in the revolt against Russia. For a short time in 1794, the Lithuanian army recaptured three quarters of the ancient territory, including Vilna. The Jewish community in Vilna swore an oath to the new provisional government on May 17, 1794.

A leader in the Jewish community, Dr. Polonus, delivered a speech at the synagogue that described the cruelty of the Russians and asked the congregation to report any information to the army's leaders about the movements of Russian troops. The Jewish community paid over 25,000 gulden towards the costs of war, and donated gunpowder, lead, and two hundred uniforms. Under siege for three weeks, many of Vilna's Jews joined the army and died taking part in the city's defense. On July 30, 1794, the

Russians re-occupied Vilna.29

Back to Top Vilna, ruled by Czarist Russia (1795-1915)The partitioning of Poland - Lithuania that divided large parcels of land between the three neighboring countries, mostly was absorbed by the Russian Empire. Within the parcel Russia annexed there was Vilna's Jewish population numbering between 5,000 to 6,000, who had been the target of intolerance by the Commonwealth's clergy, nobles and tradesmen. However, the czars of Russia were worse by far.30 At the time of the first partition of the Polish - Lithuanian federal state in 1791, Czar Catherine II (1762 - 1796) established the Pale of Settlement.

Back to Top Alexander II succeeds Czar Nicholas IAlexander II succeeded Czar Nicholas I. The new czar was both liberal minded and progressive. Czar Alexander II instituted reforms, officially abolishing the serfdom of the Russian masses, creating a modern judicial system and granting self government to rural communities. In a series of limited rights granted to the Jewish community, the czar ended military conscription of Jewish youth, and permitted the higher educated, military families, and certain professions to assimilate

and live outside the Pale of Settlement.34

Back to Top Vilna, the "Jerusalem of Lithuania""To think there are 333 Jews in one city who know the entire Talmud by heart! Why this is equivalent to the 'Jerusalem of the diaspora!'"35 Head of the Jewish "Council of Four Lands"

Seventeenth Century Legend

Even today after its destruction, world Jewry continues to refer to the city of Vilna as the 'Jerusalem of Lithuania.' However, during the seventeenth century it was thought of as a city of 'illiterates and boors' and was refused membership into the "Council of the Four Lands." Not until the Jews of Vilna presented a parchment scroll to a convention in Grodno was their membership considered. The scroll of parchment signed by the entire Vilna Rabbinate indicated that there were 333 scholars who had memorized the Talmud by heart. The head of the Rabbinic Council was so amazed by the piety, Torah-study and higher learning that he proclaimed Vilna was the 'Jerusalem of the Diaspora.' Publications written by literary and Talmudic scholars during the early to mid-seventeenth century spread throughout the Jewish communities of Europe that broadened the expertise of Rabbis to the extent that Isaiah's famous quote "from Zion will issue Torah" was rephrased to read "from Vilna will issue Torah." As legend has it, that is how Vilna became known as the 'Jerusalem of Lithuania.'36

However, there are other legends that have carried through the centuries. During the reign of Czar Alexander I, France captured the city of Vilna for a brief period from June 28, 1812 to July 16, 1812. Napoleon Bonaparte, along with his advancing army marched from the banks of the Nieman at Grodno and through the Rudnicki forest to invade Russia, and briefly settled in the city of Vilna on his way to Moscow. Upon his retreat, Napoleon re-entering the city of Vilna on November 23, 1812 saw the Great Synagogue, and has been reputed to exclaim, "Vilna, is the Jerusalem of Lithuania!"

Vilna's Jewish community had become well established and the courtyard of the Great Synagogue was a bustling hub of intellectuals, poets, and Talmudic scholars. Vilna's Jews had been influenced by the famous eighteenth century scholar Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, also known as

Vilna Gaon. Through the Gaon's leadership in advanced rabbinical

and secular studies along with the Enlightenment movement that came from Berlin through Moses Mendelssohn, Vilna gained the reputation for its intellectual and cultural spirit. Since the Vilna Gaon differed in his teachings and philosophies with the Baal Shem Tov, the Jews of Vilna were progressive--they studied mathematics, science, history, geography, literature, poetry and the arts.37

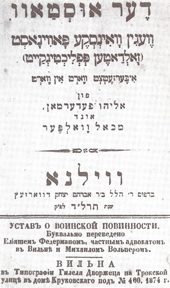

The Romm Printing Press was established in 1789, and was based in Vilna, with a second print shop in Grodno. Over generations the business grew and became the largest printing house, store and publishing business known to world Jewry. The Romm family distributed the largest body of rabbinical and scholarly work within the Yiddish-Hebrew world during this period--including the Talmud, Mishna, Bible and various other important secular texts.38

In 1893 Matthias Strashun, a Talmudic scholar, founded a large private library of Jewish literature with his fortune that was preserved under his name with 7,000 volumes bequeathed to the community. The Strashun collection became a part of a five story building named the Strashun Library that was located inside the courtyard of the Great Synagogue. At the close of the century, the Jewish community of Vilna had grown to nearly 63,000, forming forty percent of the city's total population. As a minority group, the Jews of Vilna became more politically minded in trying to establish trade, work, and property rights. The Jewish Labor Bund and the Hoveve-Zion societies, forerunners of Zionism, were established.

In addition to the various yeshivas that sprang up were modern secondary and higher institutes of learning that focused on the instruction of Yiddish and Hebrew languages. Such institutes of study inspired a list of prominent scholars, writers, and poets. The writers group Young Vilna included such names as: Max Weinreich, Zalmen Reyzen, Max Erik, Moyshe Kulbak, Chaim Grade, and Abraham Sutskever.39 By the nineteenth century Vilna

was a hub of Jewish culture, with Yiddish newspapers, publishing firms, and printing presses.

Notes:1. Dawidowicz, From that Place and Time, xiii.

2. Ibid.,

3. Josef Mermelstein, Michael Bart's friend's father who lived in the same hometown as his father, told him in a phone conversation on Oct. 2007.

4. It is estimated that 94 percent of Lithuanian Jewry was murdered during the Nazi occupation. In 1958, the Einsatzkommando trial in the Soviet Union documented the Nazi's genocidal actions--nearly 207,000 out of 220,000 Lithuanian Jews were murdered. Harran, Marilyn The Holocaust Chronicle: A History in words and Pictures, 246, 259, 671; Lithuanian collaborators: "snatchers" and "riflemen." Kruk, The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania: Chronicles from the Vilna Ghetto, 60. Kruk writes in his diary: "the snatching of organized groups who were intended to work for the Germans has become a daily event...The Germans respond that they don't know anything about the matter, and the Lithuanians respond that they have orders...Meanwhile the Jews fall victim;" Kruk, 224. Kruk writes in his diary: "A Living message from Ponar...In front of the grave stood six Lithuanian soldiers with rifles. The victims stood in rows of six, and as soon as a row was arranged, a Lithuanian gave an order, there was a salvo, and six people fell into the grave. Another row of six was driven up, again shots...and so on;" Sakowicz, ED. Yitzhak Arad, Ponary Diary (1941 - 1943) A Bystander's Account of a Mass Murder: This diary is written by a Polish man that lived in a cottage above the extermination site at Ponary. From his home he was able to view the daily shootings carried out by Lithuanians who manned the firing squad at Ponary. Refer to the diary's index: Lithuanian collaborators; For German documents on the Wannsee conference regarding Lithuanian collaboration: go to http://fcit.usf.edu/holocaust/resource/document/DocJager.htm -- The German documents state: "Security police duties in Lithuania taken over by Einsatzkommando 3 on

2 July 1941. The Wilna [Vilnius] area was taken over by EK 3 on 9 Aug. 1941...Up until these dates EK 9 operated in Wilna...

Following the formation of a raiding squad under the command of SS-Obersturmfuhrer Hamman and 8-10 reliable men from the Einsatzkommando, the following actions were conducted in cooperation with

Lithuanian partisans: EK 3 detachment in Wilna:

12.8-1.9.41 City of Wilna 425 Jews, 19 Jewesses, 8 Comm. (m.),

9 Comm. (f.) 461

2.9.41 City of Wilna 864 Jews, 2,019 Jewesses, 817

Jewish children (sonderaktion because

German soldiers shot at by Jews) 3,700

12.9.41 City of Wilna 993 Jews, 1,670 Jewesses, 771

Jewish children 3,334

17.9.41 City of Wilna 337 Jews, 687 Jewesses, 247

Jewish children and 4 Lith. Comm. 1,271

4.10.41 City of Wilna 432 Jews, 1,115 Jewesses, 436

Jewish children 1,983

16.10.41 City of Wilna 382 Jews, 507 Jewesses, 257

Jewish children 1,146

21.10.41 City of Wilna 718 Jews, 1,063 Jewesses, 586

Jewish children 2,367

25.10.41 City of Wilna 1,776 Jewesses, 812 Jewish children 2,578

27.10.41 City of Wilna 946 Jews, 184 Jewesess, 73

Jewish children 1,203

30.10.41 City of Wilna 382 Jews, 789 Jewesses, 362

Jewish children 1,553

6.11.41 City of Wilna 340 Jews, 749 Jewesses, 252

Jewish children 1,341

19.11.41 City of Wilna 76 Jews, 77 Jewesses, 18

Jewish children 171

19.11.41 City of Wilna 6 POW's, 8 Poles 14

20.11.41 City of Wilna 3 POW's 3

25.11.41 City of Wilna 9 Jews, 46 Jewesses, 8 Jewish

children, 1 Pole for possession of arms

and other military equipment 64

...Today I can confirm that our objective, to solve the Jewish problem

for Lithuania, has been achieved by EK 3. In Lithuania there are no more

Jews, apart from Jewish workers and their families...(signed) Jager

SS-Standartenfyhrer"

5. Arad, Ghetto in Flames, 215.

6. Fishman, Embers Plucked From the Fire., 7.

7. Cohen, Vilna, 10. Israel Cohen writes in his Preface that his book published in 1943, as far as he was aware, was 'the first comprehensive history, in any language, of the Jewish community of Vilna from its earliest times.' Ironically, Cohen wrote about the history of the Jews in Vilna during the destruction of Vilna's Jewry (1941 - 1944). His information in large part is based on the books and brochures that he acquired with the help of a scholarly librarian at the Strashun Library while visiting the city fifteen years prior. In regards to the city's name Cohen writes, prior to WWI the Russian spelling Wilna was 'fairly universal', when the Poles controlled the city the name was Wilno. During the brief occupation by the Lithuanians it was Vilnius, and under German authority the spelling was again Wilna. But 'the pronunciation in English speaking countries has always been Vilna, and that too is the pronunciation in Jewish circles'.

8. Cohen, Vilna, 2, 3, 6; Dawidowicz, From that Place and Time, 33 - 34.

9. Cohen, Vilna, 3.

10. Ibid., 6 - 7.

11. Ibid., 8 - 9.

12. Ibid., 16.

13. Ibid., 15.

14. Cohen, Vilna, 11 - 12; Levin, The Litvaks: A Short History of the Jews in Lithuania, 48 - 49.

15. Cohen, Vilna, 24 - 28, 30, 91, 103.

16. Ibid., 41.

17. Cohen, Vilna, 44; Beitler Family Foundation, The Timechart History of Jewish Civilization, 8.

18. Cohen, Vilna, 47 - 49.

19. Ibid., 99.

20. Beitler Family Foundation, 8: The first blood libel case took place in Norwich, England in 1144; Cohen 54: The first case of "ritual murder" in Lithuania was in 1680. Due to religious fanaticism within the local population, a family and five of the Jewish community leaders were condemned to death with an allegation of "ritual-murder" handed down by the Vilna Tribunal and again ten years later three more Jews were charged and convicted of "ritual-murder" in Vilna and Bialystok.

21. Cohen, Vilna, 57.

22. Ibid., 56 - 57.

23. Ibid., 58 - 59.

24. Ibid., 64.

25. Ibid., 68.

26. Cohen, Vilna, 84; Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760 - 1850, 586.

27. Kostanian, Jewish Life in Lithuania, 39.

28. Dawidowicz From that Place and Time, 30.

29. Cohen, Vilna, 86 - 87, 282; Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, XIX; Dawidowicz From that Place and Time, 30.

30. Ran, vol 1, Jerusalem of Lithuania, XIX; Gutman, The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, 895 - 896.

31. "Pale of Settlement, Jewish." Britannica Student Encyclopedia, Online. 2 Feb.

32. Cohen, Vilna, 266 - 267, 270 - 271, 274 - 275.

33. Ibid., 282.

34. Ibid., 284.

35. Kowalski, A Secret Press in Nazi Europe, 25.

36. Ibid., 25 - 27.

37. Cohen, Vilna, 223, 263; Dawidowicz, From that Place and Time, 33, 43 - 45.

38. Cohen, Vilna, 328 - 330, 223.

39. Ibid., 315, 410; Ran, vol 1, Jerusalem of Lithuania, XIX; Dawidowicz, From that Place and Time, 38

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vilna, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania - Page 1 of 6