Life in the Vilna Ghetto

"A beautiful, sunny day has risen. The streets are closed off by the Lithuanians. The streets are turbulent...Soon we have our first view of the

move to the ghetto, a picture of the Middle Ages--a dark gray mass of people goes harnessed to large bundles. We understand that soon our turn

will come. I look at the house in disarray, at the bundles, at the perplexed, desperate people. I see things scattered which were dear to me...Suddenly everything around me begins to weep. Everything weeps."1

Extract from 13-year old Yitskok Rudashevski's Diary

Vilnius, September 6, 1941

Vilna, the 'Jerusalem of Lithuania'

Over Ninety-six percent of the Jews living in Vilna were murdered during the Nazi occupation. No other Jewish community in Nazi-occupied Europe was so comprehensively destroyed. The majority of the city's Jews were shot by Einsatzgruppen A and their local Lithuanian collaborators at Ponary, a forested area just outside the city.

Vilna, known today as Vilnius, Lithuania is located in one of three Baltic States of Eastern Europe. On the eve of World War II the city was under Polish rule, and was referred to as Wilno. The city

|

Vilna Overview

* Bart collection / Leyzer Ran

|

|

Choral Synagogue

* Bart / Leyzer Ran

|

had a population of about two hundred thousand that comprised of a culturally diverse mix of people. 2

Thirty percent of Vilna's inhabitants were Jewish, numbering nearly sixty thousand. There were 106 synagogues,

including the Choral Synagogue which is the last remaining synagogue in Vilnius today. Overwhelmingly, the city of Vilna had a commanding Catholic presence

that made up sixty percent of the population--mostly Poles and some Lithuanians. There

were a few other religions represented in the city including: two Protestant (one Lutheran, and one Calvinist) and two Russian

Orthodox churches. The ethnic minority consisted of Lithuanians, Belorussians, Russians, Ukrainians, and a few others. After the Poles, the Jews remained the largest ethnic and religious group

in Vilna prior to the war. 3

The Rippentrop-Molotov Pact

On August 23, 1939, the Russians and Germans signed the Non-Aggression Pact dividing Poland between them. One week after the agreement was signed, Nazi Germany invaded western Poland. On September 19th the city of Vilna,

located to the east, was overrun by Soviet troops. Several weeks later, the Soviets signed a mutual assistance pact handing over control of the city to the Lithuanians.

|

New York Times

* Frank Capra

|

Vilna's Jews initially welcomed both the Soviets and the subsequent Lithuanian administration,

since this meant the city would not be ruled by the Polish Endeks or fall under the occupation of Nazi Germany. Some fourteen

|

Cheap Houses

* Leyzer Ran

|

thousand Jewish refugees from German occupied Poland made their way to the city, including 1,400 young

Zionists--some of whom found a place to live at the 'Cheap Houses' on 37 Subocz Street located on the outskirts of the city. By June 1940 the city of Vilna, under Lithuanian control, was in chaos and was marked by anti-Jewish riots, soaring food prices, and growing tension amongst the populace that caused the Soviets to incorporate Lithuania back into the Soviet Union making it apart of the Soviet republic.

The Soviet regime outlawed the activities of Jewish organizations and political parties, and took over

Jewish schools and cultural institutions. Jewish studies, religion, and history were prohibited.

Businesses with over ten employees were nationalized, bank deposits were frozen and anyone having a tie to the government

was sent to Siberia, deep into the Soviet Union. During this period some Jewish refugees left Vilna

for Palestine; some were granted travel visas by Consul Sugihara stationed in Kaunas, Lithuania

for Curacao (the Dutch West Indies) through Japanese occupied Shanghai; and several thousand were able to flee into the Soviet interior. The remaining Zionist youth movements, deemed illegal by the Soviets, organized themselves in various ways into underground organizations within the city. The HaShomer Hatzair divided the membership into smaller cells consisting of four or five members who worked and lived together. 4 At this time, Vilna's Jewish population was about 80,000. 5

The Nazi Invasion

|

German Invasion

* Ghetto Fighters' House /

ARC

|

Hitler then broke the Non-Aggression Pact with Stalin. The Nazis began to bomb Vilna on June 22, 1941,

and several days later the German army Wehrmacht occupied Vilna. Close behind was Einsatzgruppe A,

whose commanding officers, the Einsatzkommandos and Sonderkommandos, main job was to kill Jews.6

A few days later, the German military authorities and the Lithuanian administration that had been established issued a series

of anti-Jewish decrees. Jews were ordered to wear a yellow star; they were not allowed to use

the sidewalks, and certain streets were put out of bounds; a night curfew was imposed; they could

only make purchases during certain times and in certain stores. In addition, a special detail, directed by Dr. Gotthardt

under the command of Reich Administrator Alfred Rosen, was ordered to round up rare Jewish book collections from the Strashun library,

the YIVO Institute, and various synagogues in Vilna.7

On July 4 the German military command ordered the establishment of a Judenrat. At first the Judenrat had nine members. Later the order came for

the membership to be enlarged to twenty four. Shaul Trotzki was chairman, and

Antol Fried was his deputy.8

|

Ponary

* ARC: Photo montage

|

Between mid July and early August, Lithuania was transferred from German military control to German

civilian administration. The mass extermination of Vilna's Jews began when Nazi Commissar Hans Hingst

was appointed governor of Vilna along with his aide de camp, Franz Murer, an "expert on Jewish questions". 9 Exploiting the anti-Semitic prejudges of the local

population, the Germans utilized local volunteers to round up and kill the Jews of Vilna.

A witness to the roundup of Jews Dr. Dworzecki later recalled,

"Gestapo [that is Einsatzkommando] men come in cars and stop outside Jewish homes. They haul the men out and order them to bring along a towel and soap. The people are ostensibly being taken to work for a few days, but they never come back. Groups of young Lithuanians and Poles appear on the streets, wearing white armbands. They round up Jews and take them to the police or jail."10

Some of the Lithuanian military men were reorganized under German command into police units and others into special units, called Ypatingi Buriai (special ones).

In July, Einsatzkommando 9, assisted by a Lithuanian 150 manned unit of Ypatingi Buriai--also referred to as snatchers--rounded

up five thousand Jewish men from the streets and houses and took them to Ponary, a wooded area about 6.2 miles south of Vilna.

The Einsatzgruppen Report No. 21, dated July 13, [1941] states,

"In Vilnius by July 8 the local Einsatzkommando liquidated 321 Jews. The Lithuanians Ordnugsdienst were instructed to take part in the liquidation of Jews. 150 Lithuanian police were assigned to this task. They arrested the Jews and put them into a concentration camp [Ponary] where they were subjected the same day to Special Treatment [Sonderbehandlung, a euphemism for killing]."11

An eyewitness to the round ups, Herman Kruk wrote in his diary on July 9, [1941]:

"The snatching of organized groups who intended to work for the Germans has become a daily event. No intervention helps. The Germans respond that they don't know anything about the matter, and the Lithuanians respond that they have orders...meanwhile the Jews fall victim."12

In the forest there were Lithuanian auxiliaries, from the Lithuanian Riflemen's Association, manning the firing squad to shoot the Jews.13 The Jews in Vilna knew nothing of these

men who were taken, there were only rumors the men were working somewhere in the east.

An eyewitness to the almost daily shootings at Ponary was a local Polish man who lived in a cottage overlooking the extermination site, Kazimierz Sakowicz wrote in his diary [July 1941]:

"By the second day, July 12, a Saturday, we already knew what was going on, because at about 3 p.m. a large group of Jews was taken to the forest, about 300 people, mainly intelligentsia with suitcases, beautifully dressed, known for their good economic situation, etc. An hour later the volleys began. Ten people were shot at a time. They took off their overcoats, caps, and shoes (but not their trousers!). Executions continue on the following days: July 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, and 19, a Saturday. The Shaulists [Lithuanians from the Riflemen's Association]

do the shootings, striplings of seventeen to twenty five years...Only the Shaulists do the shooting and guarding."14

On August 6, the new German administration imposed a levy of 5 million rubles--500,000 reichmarks--on the Jews.15

In an Aktion carried out from August 31 to September 3, 1941, eight thousand more Jews including most of the members of the Judenrat were

taken to Ponary and murdered by the German S.S. and an armed unit of para-military Lithuanians. This Aktion became

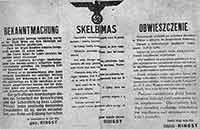

|

Wielka Street

* Bart Collection

|

|

Lithuanian Newspaper

* Leyzer Ran

|

known amongst the Jews as the Night of the Great Provocation since it was preceded by the Germans staging

an attack on German soldiers on the corner of Wielka & Szklanna, blaming it on the Jews that was broadcasted by government radio 5 to 6 hours prior to the supposed incident, and presenting the Aktion that followed as

a retaliatory move. 16 The day after the staged incident and Aktion, an announcement was published in the local paper signed by Nazi Commissar Han Hingst that states:

"Yesterday, on Sunday afternoon someone shot at a German soldier in Vilna. Two of the cowardly bandits were arrested. They were Jews.

The culprits have forfeited their life. They were shot immediately. To prevent such hostile actions, strict countermeasures have been already adopted.

The retaliation will hit all of the Jews. For the time being all Jews, regardless of sex, are not allowed to leave their quarters between 3pm and 10am

except those Jews who are expressedly ordered for work deployment. These orders serve for the security of the population. It's the duty

of each respectable thinking person to help law and orders prevail."17

The Regional Commissioner of Wilna

signed Hingst

In the following days, from September 3 to 5, the area from which the Jews had

been evacuated for the Aktion was fenced in and two ghettos were set up. During the course of the

summer, German troops along with Lithuanian collaborators killed more than 35,000 Jews living in

Vilna in a rapid extermination program. A notice in the Lithuanian newspaper New Lithuania published an article about

establishing a ghetto for the Jews of Vilna. 18 On September 6, 1941 the Nazis herded the remaining

35,000 Jews into the perimeters of two ghettos.

Jews all over Vilna were given notice to evacuate their homes, in some cases families were given

5 minutes notice to leave the homes they had known for generations. The Jews were forced,

from their homes, and walked to the newly formed ghetto carrying very few possessions,

being beaten by the German S.S. 19

The Vilna Ghetto

Ghetto One and Ghetto Two were sealed and separated from each other by Deutsche (German) Street.

|

Ghetto's Main Gate

* Leyzer Ran

|

|

Jacob Gens

* Leyzer Ran

|

On September 6 all the remaining Jews of Vilna were forced to move into the ghettos--about twenty five

thousand into Ghetto One and about ten thousand into Ghetto Two. Another six

thousand were taken to Ponary and shot. On the following day the Germans established two Judenrats,

one for each ghetto. Antol Fried was appointed chairman in Ghetto One. The Judenrat set up departments

for food, health, lodging, education, and employment. The Judenrat building was

located on Rudnicka Street. 20 A Jewish police force was also established,

with Jacob Gens as the commander--pictured to the right. Under his command, Mier Levas headed the

Jewish gate guards at the ghetto's main entrance. The main gate was a focal point of tension for ghetto prisoners. After a long days work, returning Jews had to pass the inspection point at the 'tower' located to the left of the gate.

It was the task of the Jewish police to check whether Jews returning from work were attempting to smuggle in what the Gestapo deemed illegal contraband--the importation of food was not allowed and failure to comply with official German command meant death.

For the most part, the Jewish gate guards stationed on the inside of the ghetto gate were able to turn a blind eye. Occasionally, Lithuanian policemen stationed on the outside of the ghetto gate searched those entering the main gate

and took what they could find. In some instances, Gestapo officers would arrive unexpectedly and conduct brutal searches of those returning from work. The Gestapo officers would take even a small piece of bread from a ghetto resident

trying to get food for his family or himself. The "smugglers" were often beaten by the Gestapo to the point that they were bleeding, then they either were sent into the ghetto or taken to Lukiszki prison and from there to Ponary for execution. 21

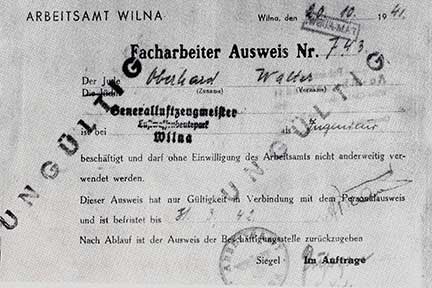

Between September 15 and October 21, families in which neither parent was employed in a place that issued work permits,

known as Scheinen, were transferred to Ghetto Two, the smaller of the two ghettos. The other families were put

into Ghetto One. On October 1, 1941, the Yom Kippur Aktion took place. After two weeks in the ghetto, thirteen year old Yitskhok Rudashevski wrote in his diary,

"The workers of

|

Gestapo during Selection

* Leyzer Ran

|

the most important working units receive professional workers' stamps on their working certificates. Those who do not receive such a certificate must move with their families to the second ghetto...Again troubled people with bundles go to the second ghetto. Today is Yom Kippur...the ghetto is full of storm troopers. They thought Jews would not go to work today, so they came to the ghetto to take them. At night things suddenly became turbulent...Lithuanians have arrived. I look at the courtyard and see them leading away people with bundles...In the morning terrible news spreads. Several thousand people were uprooted from the ghetto at night. These people never came back again." 22

In three more Aktionen, on October

3-4, 15-16, and 21, Ghetto Two was liquidated and its inhabitants taken to Ponary and murdered. Pictured to the left is a schein, a schein

meant life. On October 23, 1941, Murer distributed 3,000 "yellow Scheinen" among the Jews in Ghetto One. A "yellow Schein"

|

Yellow Schein

* Leyzer Ran

|

enabled its bearer to register on it another parent and no more than two children under the age of sixteen. This presented an agonizing dilemma

for the holder of a schein. Which family members were to be saved? The holder had to choose between a parent, spouse, and children, or siblings. 23

The Germans planned to permit a maximum of 12,000 Jews to remain in the Vilna ghetto, out of the total of

27,000 to 28,000 surviving in Ghetto One at that time. On October 24 and November 3-5 the yellow Schein

Aktionen took place, followed in December by further Aktionen on a smaller scale, the last on December 22. After hiding in an attic in the ghetto for six hours, thirteen year old Yitshkhok Rudashevski wrote in his diary,

"We creep out of the hide-out after a six hour imprisonment. Everything resembles the aftermath of a catastrophe. On the pavement lie bundles, a bloody reminder of the people who have just been dragged away to their deaths. Some of those taken were led away to the second ghetto. The largest part to Lukishki [prison], and from there to Ponar. Ponar--a slaughter house for thousands of Jews. Ponar is soaked in Jewish blood. Ponar is the same as a nightmare...Ponar is passive death, the word contains the tragedy of our helplessness. No! We shall not go to Ponar. The mood of the slaughter has not yet disappeared. What has been will soon be repeated."24

By the end of 1941, the Germans had killed more than half of the population who had been in Vilna at

occupation. A total of 12,000 were left without the protection of a yellow Schein, plus another 8,000 went

into hiding. Another 3,500 had either fled to other nearby cities where Jews were still living in

relative safety, or had found a place to hide outside the ghetto.25

For about a year, between the spring of 1942 and the spring of 1943, there were no mass Aktionen. The

ghetto, under the direction of Jacob Gens became productive, with most of its inhabitants employed in jobs

outside the ghetto. The Judenrat felt that if the ghetto was productive in serving the German's war interests,

the Germans would keep the ghetto intact.

Jacob Gens, a dominate figure in the ghetto leadership as the Jewish Police Commander, replaced

Anatol Fried as Judenrat chairman.26 The Nazis ordered the establishment of a work group of twelve that were later nicknamed the 'paper brigade'. Made up of intellectuals, the work group was ordered by the Nazis to send seventy percent of the

rare books that had previously been rounded up brought to the paper mill for disposal and the rest shipped to Frankfurt Germany's Nazi

Institute for the Research into the Jewish Question. Jewish intellectuals, such as Herman Kruk, began hiding the rare books in various places.

Since the Germans did not know how to read Yiddish or Hebrew writing, the books' fate was based on the attractiveness of the bindings. The work group's members, who began saving the cultural treasures,

were motivated by a quote made by Cicero given in a speech in 1891 by Simon Dubnow who initiated the preservation of rare book collections throughout Eastern Europe:

"not to know history means to remain forever a child." His maxim was to be applied to entire nations as well as individuals.27

Although most ghetto Jews worked, the ghetto had schools; a rich cultural life,

including a theater that starred actress and singer Chayela Rosenthal and a Hebrew choir that was conducted by Volf Durmashkin. 28 The ghetto choir sang songs such as

"Never Say" written by Hirsh Glik, a member of the Vilna ghetto underground.

"Never say you are walking your last road,

|

Hebrew Choir

* Leyzer Ran

|

though leaden skies conceal the days of blue. The hour that we

have longed for will appear, our steps will beat like drums announcing we are here! From the lands of flowering palms to distant lands of snow,

we gather here with all our pain and all our woe. And where our blood has spilled and sacrificed in vain,

Brave men will rise and carry on in our name. The morning sun will shine on us one day; our enemy will vanish

and fade away. But if the sun and dawn come too late for us, from generation to generation let them be singing this song.

This song is written with our blood and not in pencil-lead, It is a song of summer birds that have no dread. Mid crumbling walls a people

took their final stand, and sang this song with leveled guns in every hand!" Click to hear song

The ghetto administration also organized social-welfare institutions such as soup kitchens; and a medical

care system that sought to combat starvation and disease. The residents of the ghetto were required to use the public bathhouse

before obtaining a food ration card. Due to organizational efforts by the ghetto administration,

the mortality rate as a result of starvation was low in comparison to other larger ghettos, such as Warsaw. The police kept order, and there was a law court.

In spring of 1943, the situation of the Jews in Vilna deteriorated. Some of the smaller ghettos in towns surrounding Vilna were liquidated. The Jews had been told they would be

moved to the Vilna and Kovno ghettos, but only a quarter reached Vilna and the rest were taken to Ponary

and shot. The liquidations of these smaller ghettos caused great fear in the Vilna ghetto.29

Notes

1. Rudashevski, The Diary of the Vilna Ghetto, 31.

2. The city of Vilna changed hands many times. "...under Russian control the city was called [W]ilna; under Polish administration Wilno; and under Lithuanian rules Vilnius. In German it was Wilna, in Yiddish Vilne, and in Hebrew Vilna." According to Shneidman, Three Tragic Heroes, xi.

3. Dawidowicz, From that Place and Time, 36 - 37.

4. Arad, Ghetto in Flames, 9, 16, 17, 21, 22 - 23, 28; Cohen, Vilna, 423; Gutman, Ed. Yitzhak Arad, The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, 1571 - 1572; Kostanian, Jewish Life in Lithuania, 19 - 21.

5. Kruk, The Last Day of the Jerusalem of Lithuania, 284; Arad, Ghetto in Flames, 212 - 213, 223; Nurenburg War Crimes Tribunal, February 27, 1946 Abraham Sutzkever said, "When the Germans seized my city, Vilna, about 80,000 Jews lived there. After the occupation 600 Jews remained in Vilna."

6. Gutman, Ed. Yitzhak Arad, The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, 435 - 436.

7. Fishman, Embers Plucked From the Fire, 4.

8. Kruk, The Last Day of the Jerusalem of Lithuania, 204; Gutman, Ed. Yitzhak Arad, The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, 1572.

9. Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, vol 2, 430.

10. Kruk, The Last Day of the Jerusalem of Lithuania, 284; Sakowicz, Ed. Yitzhak Arad Ponary Diary 1941 - 1943. A Bystander's Account of a Mass Murder, 12: "Lithuanians who manned the firing squad at Ponary. The sauliu sajunga (Riflemen's association) had been a paramilitary nationalist organization before Lithuania fell into Soviet hands. Many of its members rose up against the retreating Soviet Army and then volunteered to save the Germans."

11. Sakowicz, Ed. Yitzhak Arad Ponary Diary 1941 - 1943. A Bystander's Account of a Mass Murder, 8; Yitzhak Arad, Shmuel Krawowski, and Shmuel Spector, eds., The Einsatzgruppen Reports, New York, 1989.

12. Kruk, The Last Day of the Jerusalem of Lithuania, 60.

13. Sakowicz, Ed. Yitzhak Arad Ponary Diary 1941 - 1943. A Bystander's Account of a Mass Murder, 8; Dworzecki, Jerusalem of Lithuania in Revolt and Holocaust, Tel Aviv, 1951, 20-21. [Hebrew]

14. Sakowicz, Ed. Yitzhak Arad Ponary Diary 1941 - 1943. A Bystander's Account of a Mass Murder, 12.

15. Gutman, Ed. Yitzhak Arad, The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, 1573; Schneidman, Three Tragic Heroes, 18.

16. Kruk, The Last Day of the Jerusalem of Lithuania, 81 - 84; Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, vol 2, 432; Gutman, Ed. Yitzhak Arad, The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, 1573; Eichmann Trial transcripts: Abba Kovner's testimony.

17. Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, vol 2, 434.

18. Ibid., 434.

19. Kruk 95-100; Arad 113; N.N. Schneidman 19.

20. Gutman 1573.

21. Ran 461; N.N. Shneidman 19, 22.

22. Rudashevski, 35 - 36.

23. Eichman Trial: Dworzecki testamony.

24. Rudashevski, 40 - 41.

25. Gutman 1573; Kruk 285; N.N. Schneidman 19-20.

26. Gutman 1573.

27. Fishman 1.

28. Kruk 271; Hirsh Glik's song Never Say is a combination of several translated versions: Kowalski 91; Yom HaShoah Program

29. Gutman 1573-1574.

|